Back in the Iron Age and the Roman and early Saxon periods – fields were tilled using ‘ard’ ploughs. These were very simple; basically a stick on a pole. They could be pulled by two oxen, but only scratched the ground, which meant the ploughman had to go over the ground again, at right angles. So fields were relatively small and square.

In the later Saxon period heavier, ‘mouldboard’ ploughs began to appear. Similar in design to modern ploughs, these could turn over much heavier soils and only needed to one pass. But they required, four, six or even eight oxen to pull them, depending on the soil conditions. These teams were difficult to turn round, so long, larger fields were more practical.

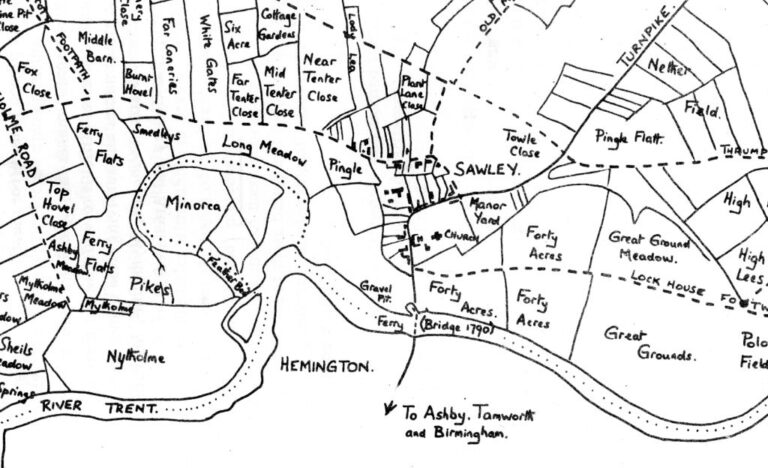

From (roughly) the 10th century to the late 18th century, most farming was organised on the open field system. Arable land in a parish was usually divided into 3 large open fields. Within these were ‘furlongs’ divided into lots of parallel strips, typically 8 yards wide and 220 yards long (hence a ‘furlong’ as a measure of length is 220 yards).

Ploughs had fixed blades which pushed the soil to the right. As the ploughing was normally done clockwise, this produced the distinctive ridges and furrows which can still be seen in many places. This had the advantage of marking the individual strips and helping with drainage. The heavy ploughs and the oxen teams were difficult to turn, so the strips developed a left twist at the ends as the plough was turned round to line up for the next run.

Villagers held scattered strips, in different furlongs in different fields, the idea being to share out the good and poorer land. One of the fields was left fallow each year. Villagers all had grazing rights on the fallow field, on the stubble after harvest and on the meadow land along the rivers. There were no hedges or fences between the furlongs, only where animals needed to be contained – at the edges of the meadows and the large fields.

The Domesday Book records that in 1086AD the parish of Sawley had 29 villager households and 13 smallholders. There were 12 ploughlands of arable land (a ploughland was the area that could be ploughed by a team of 8 oxen in a year). But there were 16 plough teams (of which 3 belonged to the lord of the manor). Maybe the apparent excess of plough teams was because they were split between the different settlements (Sawley, Wilne etc) or perhaps the ground was particularly hard to work. The parish also had 30 acres of meadow and just 3 x 1 furlongs of woodland.

By the mid 18th century the Earl of Harrington was the lord of the manor. Although some of the Earl’s land was already enclosed, the Sawley Enclosure Act of 1787 divided 800 acres of open fields between 35 people, though most of these had less than 10 acres each. The Earl of Harrington was allocated over 200 acres. John Towle of Sawley received more than 100 acres. The enclosure acts disadvantaged poorer farmers but did improve farming efficiency and provided surplus food and labour for the industrial revolution. They also created the hedgerows that now characterise the English land. It was noted at the time that the fields near the Trent were never ploughed but kept as pasture as it was thought that better cheese was produced from cows fed on natural grass. Sawley and Wilsthorpe both had pigeon houses (for meat).

Even in Victorian times, all the villagers helped with the harvest. They started between 3 and 4am and carried on until dusk, with a rest for lunch. Harvested grain was milled at the windmill near what is now the start of Hawthorne Avenue.

Wages were low, but every farmer allowed gleaning after the main harvest. This allowed poor families to collect any leftover grain to store in their homes and attics. After threshing and winnowing, this grain was made into frumenty, which was something like porridge. It was eaten hot with milk (which was plentiful in Sawley) and sweetened with treacle or sugar.

Stray, stolen or lost cows , and other animals, were placed in the pinfold on Cross Street, opposite the National School. They were kept there until ownership was established and payment for foddering detention was made. George Wilmot was the keeper and received 4½d to let them out (more if they had been fed).

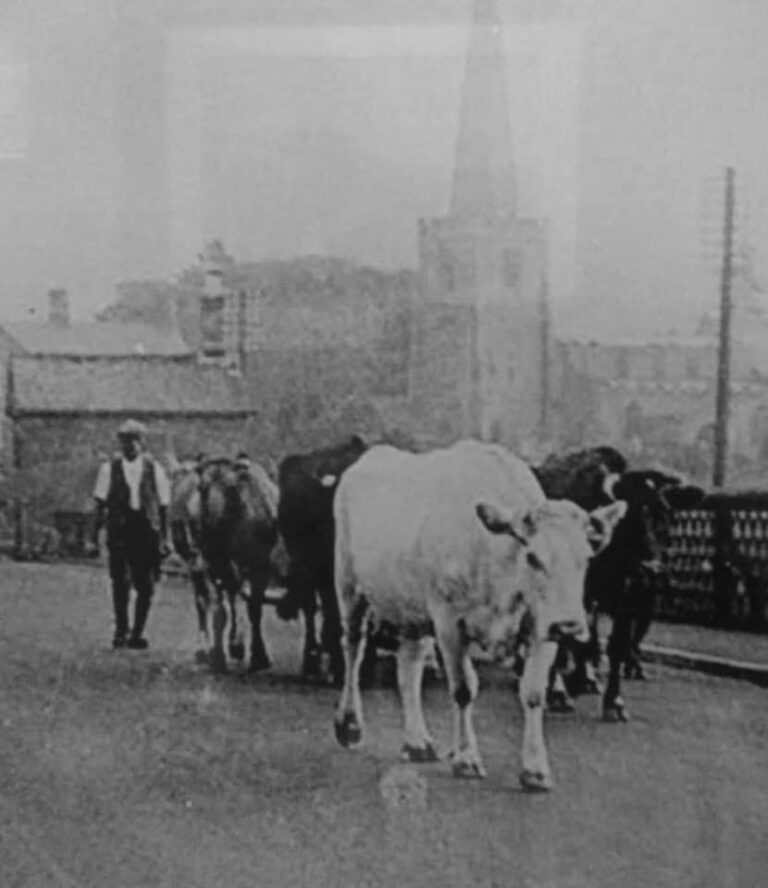

In medieval times only oxen* were used to pull ploughs and carts. They were gradually replaced by horses, especially after the Enclosure Acts, as it was much easier to turn a team of horses round in the smaller fields created by enclosure. So the change from oxen to horses probably happened in Sawley in the late 18th century.

By 1827 Sawley had 14 farmers, including 3 generations of the Smith family. In 1851 there were 18 farmers, with 74 men and boys and 6 women and girls employed in farm work. Some of the farmers had other jobs, including baker, grocer, maltster and innkeeper.

See also: Farms

(*) Oxen are bullocks trained as draft animals. Oxen is the only remaining English word that still uses the original Anglo Saxon plural suffix ‘en’ instead of ‘s’ (although ‘children’ uses a version of it).