By Geoffrey Kingscott

I was only three years old when the war started, and so have no pre-war memories at all.

My parents often recalled the fear of gas attacks which everyone had, so the day after war was declared my father picked all the pears from the large pear tree at the back of the house.

My earliest memory is of standing at the front gate of the house watching a bricklayer laying the lower courses of what became the street air-raid shelter. Another early memory is seeing workmen using an oxy-acetylene torch (an item of great wonder) to remove the railings from the front fence of Mrs Powdrill’s house (no. 17 Shaftesbury Avenue).

We shared with four other families to have our own air-raid shelter, built in our garden. I cannot remember it being built. I have one memory of being picked up out of bed by my father to be taken down to the shelter, and another of looking down from the top bunk. The grown-ups were talking in low voices, and I think there was an electric fire with one bar, so there must have been electricity.

I recall a snatch of adults’ conversation outside the shelter after the all-clear one night, discussing whether the red sky was an indication of Coventry burning “again”. I also recall having my own gas mask in a cardboard box, and the rubbery smell when you put the gas mask on.

Instead of blackout curtains Dad had cut to size some wooden boards which slotted into nails round the window.

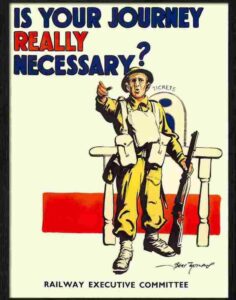

We often went to visit my aunts and cousin in Derby. I remember the barrage balloons above Derby station, and the poster “Is your journey really necessary?” at Sawley Junction station, which, being literally minded, used to worry me.

On one occasion during the blackout an Aunt, on her way to visit us, thought she had arrived at Sawley Junction station. However, the train had just stopped for a signal at the disused Old Sawley station, which still had its platforms. She discovered her mistake in time to scramble back into the train.

Having grown up not knowing anything but war, the blackout, rationing and air-raids all seemed perfectly normal. Adults would sometimes talk nostalgically about the wonders of peacetime, but that seemed a far-off never-never land. There was a still-life picture showing an apple, an orange and a banana, and this picture was always pointed out to me. I was given the impression that bananas were something truly special. To this day I can never quite get over the disappointment when eating a banana that I first experienced when, presumably after the war, I was given one for the first time. Ice-cream was the other pre-war delicacy that adults used to talk about, and somehow that was not so disappointing.

Dad worked shifts, in the railway control office at Derby station. When he was working nights and was sleeping during the day I was admonished if I made any loud noises, and soon it became second nature to creep out, speak quietly and not slam doors.

Earle from the Canadian branch of the family used to visit occasionally. He had a loud booming voice, and Dad (sleeping in the daytime because he may have worked a night shift) would always be woken by it. On one occasion Uncle Earle brought me different – unrationed! – sweets from what I was used to. This included chewing gum, which I had heard about but not previously seen. In my innocence I swallowed it. Mother was quite worried by this, but no harm seems to have been done.

In the later years of the war, we used to go on holidays to a farm in Anglesey where, as my parents never stopped saying, you would not know there was a war on. They were particularly enthused by the easy availability of eggs, including duck eggs. I had not previously been conscious of egg rationing, but I have a fleeting memory of the breakfast plates being brought in and the delight at the fried eggs

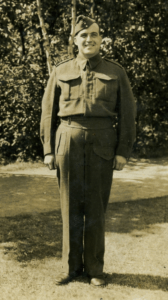

Dad had been blinded in one eye in a boyhood accident, and in 1918, to his mortification, had been turned down for the Army in the first world war. He therefore volunteered for the Home Guard. I remember the uniform hanging in the downstairs toilet, with the ‘Sherwood Foresters’ shoulder flash. We still have his forage cap, but I believe that after the war he wore the battledress for gardening till it wore out.

On one occasion the Home Guard went to practise at the rifle range near Trent Station, and afterwards were waiting in the station waiting room for the train back to Sawley Junction, when one of the rifles, which someone had forgotten to unload, went off and a bullet went through the ceiling. Dad told me this anecdote one day much later when we happened to be at Trent.

To children the build-up to D-Day meant convoys. We were taught that nothing must interrupt a convoy, and that we should not try to cross the road if a convoy was in sight. “Convoy, miss” was an accepted reason for being late for school.

I cannot recall the war having much influence on our schooling. I do remember that the corridor at Mikado-road School had a poster exhorting children to go out and collect hips and haws from the hedgerows to help with jam-making, but it was not something I ever actually did.

I think I must have moved up to Tamworth-road school by 1944, because I remember that for a time we had large numbers of evacuees there, from London. I regret to say that we disliked them intensely, and the two sets never mixed. They seemed rougher and more street-wise than we were.

As children we were vaguely aware that something terrible had been discovered at a place called Belsen. With the insensitivity and lack of understanding of young children we thought it a joke to refer to our school as ‘Belsen’. I cannot remember ever being really aware what the horrors were. As we had been taught that Nazis were bad people anyway, we did not appreciate that the shock of the discovery of a new level of vileness.

It was only towards the end of the war that I began to be aware of its progress. I cannot remember anything about D-Day, but I can remember the Richard Dimbleby radio broadcast of the crossing of the Rhine. The feeling that our side was winning was a source of great satisfaction to everyone. Somehow for we children the winning streak continued after the war when Derby County went on to win the FA Cup in the first post-war Cup Final.

The radio was of course important. There were comedy programmes for each of the three services: Stand Easy for the army, with Charlie Chester, Much Binding in the Marsh for the RAF, with Richard Murdoch and Kenneth Horne, and something for the navy whose title I forget. All comedians had catchphrases, which were much repeated. Robb Wilton would always start with the same phrase: “The day war broke out, my missus said to me…” Many of the radio personalities were also featured in a comic which was called, I think, Radio Fun. But undoubtedly the high spot of every week, the one broadcast never to be missed, was ITMA, with Tommy Handley, and a whole host of characters, each with their catchphrase; “I don’t mind if I do”, “Can I do you now, Sir”, “TTFN” (=Ta-Ta For Now), “After you, Claude; “After you Cecil”. There was even Fünf, the German spy: “Thees ess Fünf speaking”.

I was probably too young during the war to go to the cinema much, however important cinema-going became in the postwar years. But I do remember going to see Will Hay in The Goose Steps Out. I recall only one scene, and the laughter in the cinema which accompanied it, where Will Hay is in Germany masquerading as a German, and when the class gives the Nazi salute to a picture of Hitler, Will Hay gives the Churchill V-sign.

Hitler was of course the great bogyman. I remember being taken down to Long Eaton by Ann Marchant, an older girl who lived next door (with Albert and Daisy Smith), and insisting on walking on the canal bank wall, from which the railings had been taken away. She did not want me to do this, and so what she said was, “You’re helping Hitler”.

For VE-Day we had a street party, followed by a bonfire on the waste ground at the end of the street. I cannot remember the party itself, but I remember one of the games was bobbing for apples in a tub filled with water. An effigy of Hitler was burnt on the bonfire.

There was another bonfire for VJ-Day three months later (I do not know whether we had a street party). We then burned an effigy of Tojo. Now even I had heard much of Hitler the great bogyman, but I had never heard of Tojo.

Such street bonfires obviously became a regular feature when Bonfire Night was revived. With what we would consider gross insensitivity today, I recall that the loudest bangers were marketed under the name of “atomic bomb”.

Italian prisoners of war who had been kept, I think, at Weston Hall, came round door to door selling rope slippers they had made in the camp. I remember Dad inviting our caller in and doing his best to be friendly, and saying “You’ll be going home soon, I expect”, while I marvelled – we were inviting one of the enemy into our very home. I remember the rope slippers in the shoe cupboard, but I cannot remember anyone every wearing them.

So, peace had come, but it did not seem all that different from war. Of course, in Sawley we had been spared much of war’s horror.