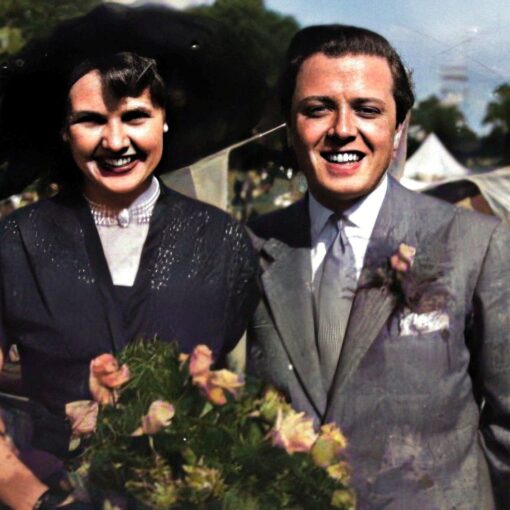

I was born in July 1939, just two months before England declared war on Germany. Our home at that time was a rented wooden bungalow on Oakland Avenue. It backed on to the Erewash Canal, and had a decent garden, so it was really a nice place to live. It was my parents’ first proper home, having lived for some time in rented rooms in Long Eaton.

My parents decided that perhaps a wooden bungalow was not the best place for a young family to be once the air raids began. Somewhat ironically, the bungalow in Oakland Avenue survived the war unscathed, but a solid brick house in Netherfield Avenue, less than a quarter of a mile from the property we moved to in Shaftesbury Avenue, was destroyed by a stray bomb and several people were killed.

l was too young to remember much about our life then but my earliest memory of all is of waking up in the air raid shelter we shared with three neighbouring families. Although two large municipal shelters would eventually be built on the street, four families had clubbed together to build a small shelter in the garden of the family opposite to us. Although neither father was absent on active service, both were engaged in war work that often kept them away from home at night.

Our father was a cable maker with Armorduct Cable Company (a reserved occupation) by day and a part-time fireman in the evening. I remember two things about these occupations. The first was going to see my father at the works off the Market Place, after my ballet lessons on Saturday mornings. Health and Safety would have a fit now, but I revelled in crawling about under the machines (switched off fortunately) collecting waste pieces of the brightly coloured cable that had been produced during the week. These could easily be twisted together to make pretty bracelets. The second was attending the fabulous Christmas parties at the Fire Station, when Santa would make his appearance down the slippery pole used by the firemen to get down from the social room to the engines below when the alarm went – something we all hoped would happen during the party.

When the bombing raids were at their height locally in 1941, our mothers would get together and decide if there was likely to be a raid that evening. If they thought so, they would put us to bed in the shelter, rather than risk having to wake us up and transfer us there if the alarm sounded later in the evening. It was of course more critical for our mother that they made the right decision as she would have to carry two sleepy toddlers across the street to reach the shelter.

The shelter itself was kitted out with, I think, two sets of wooden bunk beds, and my earliest memory is of waking up on a lower bunk and seeing my mother sitting in a wooden armchair. She was telling the boys sitting up one of the top bunks, not to make so much noise for fear of waking me up. Our mothers told us much later of standing outside the shelter and seeing the night sky lit up by all the fires burning in Coventry, some thirty miles away, after heavy raids by the German Luftwaffe.

The street shelters remained for some time, half blocking the road, but as only one family in the street – that of the manager of the Long Eaton Co-operative Society – had a car and most of the rest of the traffic was horse-drawn, they were not too much of a hindrance. There was at least one accident however, when a certain little girl, about eight years old, decided she would ride her two-wheeled “fairy” cycle down the street with no hands — a newly-acquired skill. All was fine until she neared one of the shelters and, with no bands on the handlebars to operate the brakes, crashed straight into it.

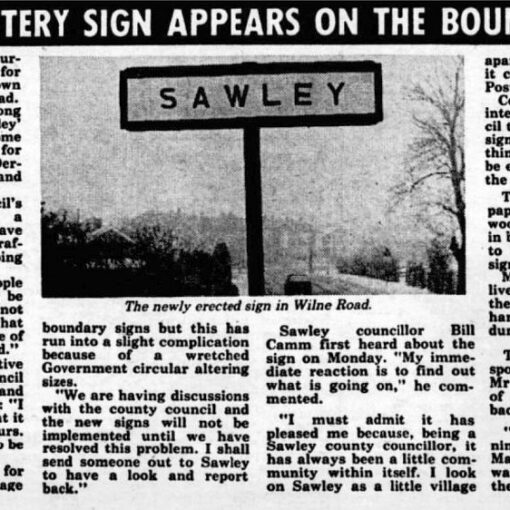

For several years after the war our coal, bread, milk and vegetables were still delivered by horse and cart, mostly owned by the Long Eaton Co-operative Society, then a thriving business in the area. Everyone knew their own Co-op number which had to be quoted for all purchases so the amount of dividend, or “divi” earned could be calculated for the twice-yearly payouts. Later, Mills, a local Sawley family, took over some of these services. Whenever a horse was in the street, many people kept an eye open, and a bucket and spade at the ready, to collect any dung that might be deposited nearby.

Originally Shaftesbury Avenue ended in open fields where we used to play and watch for skylarks, but the post-war building of council houses turned the fields into a housing estate. We lost our skylarks but for a time gained secret passages as the foundations for the new houses were dug and half-filled with concrete. There was just enough room for children to wriggle along for super games of hide and seek.

Another game involved most of the street gang. During the war all streets had a communal pig bin into which every family was expected to deposit any unwanted scraps of food (with rationing in force, there was not much food left over but, as the saying goes these days, “every little helps”). These bins were emptied regularly and taken to farms for the contents to be boiled up as swill to be fed to the pigs. One day, the bin was taking on another role, as wickets for our game of cricket. One of the boys shouted to us to take cover as he had spotted the local “bobby” turn into the street on his bike, and this particular policeman was known to object to the pig bin being used in this way. We scattered to seek protection behind gates and fences, all to no avail — we soon heard words from the street, “Just because I can’t see you doesn’t mean I don’t know you’re there!”

A highlight of the year was Guy Fawkes night. All the street gangs collected flammable materials for their own street’s bonfire, and some raided neighbouring streets to “borrow” some of their stuff. They also pestered neighbours with requests for “Penny for the Guy”, usually a scarecrow-like figure dressed in old clothes and seated in a trolley or baby’s pram. The fires were mostly communal affairs, with parents joining in, not just to supervise the dangerous business of lighting the fire and setting off the fireworks (now back on sale after years of unavailability during the war), but also to provide the other essential ingredients of toffee apples and jacket potatoes. We were lucky to have a piece of waste ground at the end of the street, conveniently next to the house of Mrs Measures, one of the providers of the last essential, rock-hard bonfire toffee.

I recall a holiday we took towards the end of the war. There were restrictions on private travel during most of the war years. Petrol was rationed, and priority was given on the railways to the transport of troops and their equipment. lt must have been in the summer of 1944, when the fear of air attacks had passed, my parents decided we could go on holiday to North Wales. Mum had made me lots of pretty dresses, despite the need for coupons to buy clothes. She bought remnants of material, cleverly cut out the shapes and sewed them together on her treadle Singer sewing machine.

Then Dad came up with an idea which spoilt my happy summer. He acquired some black lace-up boots for me to wear whilst walking in the mountains. But they weren’t proper walking boots, so Dad cut a bicycle tyre into strips and nailed these on to the soles of the boots to give more grip. That was alright, but then he made me wear the heavy boots to school “to walk them in” that is, to soften them and get my feet used to them. I was mortified, and so embarrassed. I remember trying to hide my feet under the table in class. Little girls did not wear trousers at that time, certainly not in summer, so the black boots were very conspicuous beneath my short dresses.

However, the journey to Wales was quite an adventure. We had to change trains several times, and often had to wait for connecting trains. Of course, all the engines were powered by steam then. At one station (it must have been Chester or Crewe) Dad took my brother and me for a walk round the station. It had lots of long platforms, not a bit like our little local station of Sawley Junction.

Trains, looking like fire-breathing monsters, appeared out of the blackout darkness. Some stopped for passengers to get off or on, before puffing back into the darkness. Others passed us at speed, leaving clouds of smoke floating through the station. As we climbed down a footbridge to another platform, we could see a train waiting there. But this train was different — it was full of soldiers in uniforms. When they saw us three the soldiers were rather surprised as we were all wearing our walking gear, in the middle of the night, with not a mountain in sight.

We soon realised thar the soldiers were not English and Dad told us they were American and were going off to fight in the war. Then it was our turn to be surprised when they said how “cute” I looked in my little shorts and the dreaded boots. They began to throw things at us, and we were delighted when we found the missiles were sweets, or candy as they called it. There was also some funny, flat, grey stuff, wrapped in paper. Dad said it was “chewing gum” but we didn’t know how to eat it and didn’t like it

As we walked along the platform, more and more soldiers appeared at the windows of their train, and more and more goodies were thrown out. Unlike England, there was no sugar rationing in America so they could have as much chocolate and candy as they wanted. It also got quite noisy, as the soldiers called to us in their funny language. We had to return to Mum and our baby brother when our train was due to leave. She was amazed to see us with our arms full of goodies, enough to last all the holiday.